Warning: This is not a blog for those of you who are already sick to death of election talk ...

The other night I went to the 30th anniversary

party of Urban Stonehenge. It’s a

peeling pink house atop Potrero Hill, right at the intersection of 26th

and Wisconsin. In 1982, a group of

anarchists, many of them veterans of the campaign to shut down the nuclear

weapons production facility in Rocky Flats, Colorado, moved in there, and it’s

remained a collective house ever since.

There are more or less four bedrooms upstairs and a basement which was

once a church (the baptismal font is still recognizable), is now a den, and in

between housed hordes of traveling activists, punks, squatters, slackers and

such like. I lived there for a year

around 1985-86, in a room that had no windows.

If it hadn’t been across from the kitchen, I would never have known when

it was time to get up. A few years

later, my friend Sheila moved into that room and put in a window, a skylight

and a loft, rendering it quite charming.

The people who live there now have much better cooking and

cleaning habits than the household I was part of, which might be why someone

who moved out last year had lived there for seventeen years.

|

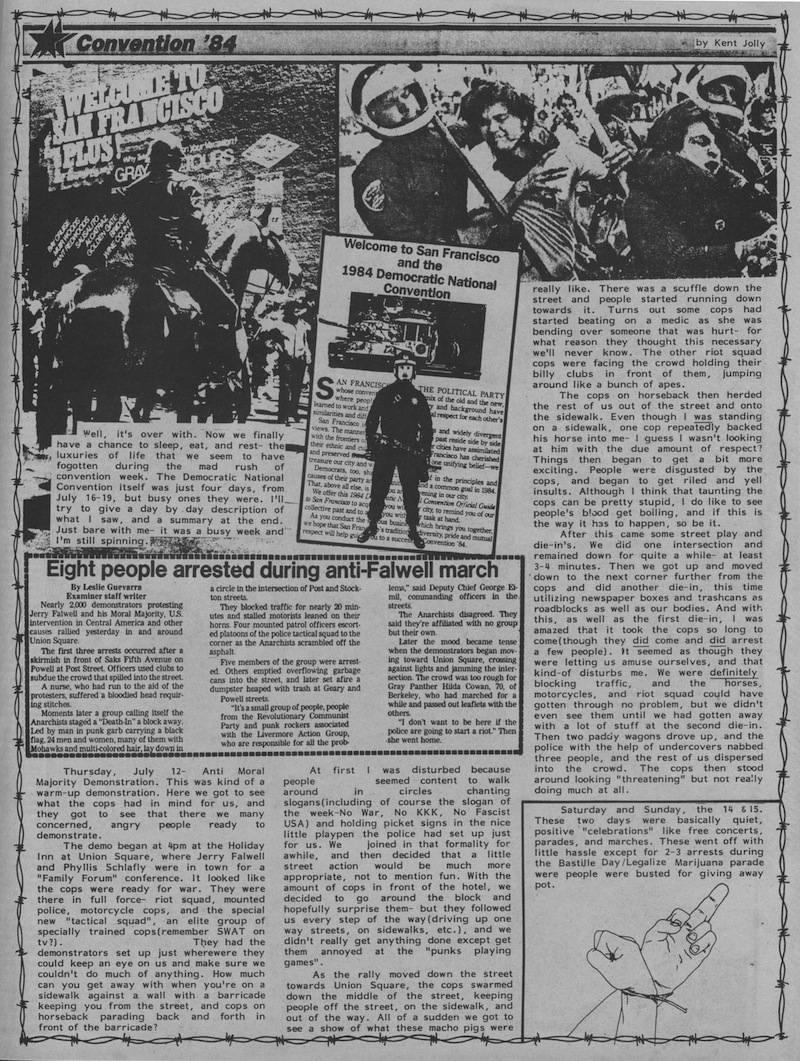

| Maximum Rock n Roll reporting on the DemCon protests in 1984 (I was there) |

“There are no undecided voters,” he said. “It’s all about getting out the vote.”

He overstated it a bit, but the general point is correct: there are many fewer undecideds than in

previous elections and despite what they claim,

the campaigns are not really trying to appeal to them. Instead they are trying

to motivate their bases to come out and volunteer.

My acquaintance went on to say that the most effective way

to get an iffy voter to the polls is a face-to-face meeting with a

volunteer. The second most effective way

is a phone call from a volunteer.

“Television ads have virtually no impact,” he said.

I wondered if that was true. It certainly flies in the face of the

now-commonplace assessment that whoever raises the most money is most likely to

win an election. Big bucks are important

for big ad buys, not for recruiting droves of volunteers to go door-to-door. I decided to look into it.

Question 1:

Is major media advertising ineffective in getting out the vote?

The effectiveness of in-person get-out-the-vote efforts

(GOTV) is undisputed,

but the question of the how and whether mass media advertising, positive,

negative, partisan or non-partisan, effects turnout is hotly contested.

Looking at evidence from the 2008 elections, Matthew

Holleque and Sarah Niebler of the University of Wisconsin political science

department conclude:

Laboratory experiments, like the ones conducted by Ansolebehere, Iyengar, and their colleagues (1994; 1997), find that exposure to negative advertising decreases the probability that people will turnout to vote. Negative campaigning, they argue, turns people off from politics and angers citizens about the tone of politics. This demobilizing effect translates into as much as five percentage point drop in voter turnout, disenfranchising approximately six million potential voters. Ansolebehere and Iyengar (1997) conclude, “In election after election, citizens have registered their disgust with the negativity of contemporary political campaigns by tuning out and staying home.”

Contrary to these findings, subsequent observational studies show no evidence that political advertising—even negative advertising—depresses voter turnout. Numerous studies posit that campaign advertising actually stimulates voter turnout, although these effects are sometimes conditional. For example, Freedman, Franz, and Goldstein (2004) find that exposure to advertising can raise the probability of turning out by as much as 10 percentage points.

Hillygus (2005) finds that all campaign effects (including television advertising) raises an individual’s probability of voting by at least 10 percent. However, despite these findings, the jury is still out on the question of whether campaign advertising affects voter turnout at all.

Many studies find that campaigning advertising has no effect on voter turnout…. While it is safe to say that campaign advertising is probably not causing millions of people to stay home on Election Day, it remains debatable whether or not campaign ads actually mobilizes citizens to head to the polls.

Question 2:

With such questionable return, why are all these super-PACs so hot to

spend millions of undisclosed dollars on TV ads?

Here are a few theories scantily clad in facts to back

them up, but not for lack of looking:

- They may not accept or even know of the hypothesis that there are not many voters to convince. When the electorate is less polarized, advertising is potentially more effective. At least one study of the 2000 and 2004 presidential elections claims to find that eliminating advertising would have cost Bush 22 electoral votes in 2000, giving Gore the election. (I say “claims to find” because not being a geek, I can’t begin to understand whether their methodology is sound. I just skip from theAbstract to the Conclusion.)

- Consultants tell them they advertising is effective. “Television and Politics – Nothing Makes a Bigger Impact,” is the headline of a 2009 article in the online magazine ElectWomen . The article is largely a rehashing of the political advice of a guy named Doug Heyl, who is, not surprisingly, “a political media adviser who develops campaign media strategies, develops and creates commercials and directs the purchase of television and radio airtime.

R. Michael Alvarez wrote in a 2011 article in Psychology Today:

… do voters pay attention? Does this barrage of political ads

influence the outcome of an election?

Candidates and political consultants think the answer to both questions is yes. For example, candidates running for office in big states like California pump amazing amounts of money into their television advertising budgets. … Recently we had a contested city council election in my home city of Pasadena, and in that race our incumbent city councilmember produced and aired a television ad in his re-election bid, and this was an election in which about 4,000 votes were cast.

But many political scientists have questioned the extent to which television advertising --- indeed, pretty much any type of campaigning --- changes voter perceptions and election outcomes.

- Ads are more important in races where the candidates are less well known. Says Ezra Klein,

If in the final days of the presidential campaign some hedge fund billionaire begins a multimillion-dollar assault on Obama, some Hollywood billionaire will probably help the president out. Either way, the ads would have a limited effect. By the end of the presidential campaign, most voters will have made up their minds. They’re not waiting for one more black-and-white clip narrated by another grim voice to push them over the edge.

In contrast, even at the end of the campaign, many potential voters will know very little about their congressional candidates. They will be susceptible to ads telling them terrible things. Some of those candidates won’t have the resources to fight back.

|

| Didn't see this on MSNBC |

- They hope to discourage voting by demoralizing the people who favor the other guy. Though polls keep finding that negative campaign ads don’t depress voter turnout, people who want to thwart democracy are nothing if not persistent.

- They keep the base energized and worried about the people who might be planning to vote for the other guy.

- They make the candidates believe they are beholden to the people who paid for the advertising.

Question 3:

If it’s all about getting out the vote, why are the Democrats (and the

Obama campaign in particular) so unworried about the people who came out for

them in droves in 2008 and are clearly not enthused about them now?

People keep saying that African Americans,

labor, Latinos and progressives have “nowhere to go,” but the fact is that

nowhere is a place, and those folks are very likely to go there. Especially since for many of them – the

Latinos and African Americans in particular – it’s getting harder and harder to

vote, something the Democrats seem fairly laconic about challenging. My acquaintance at the party claimed that

wasn’t true, that the Demos have filed suits in every state where there are

photo ID laws and discriminatory restrictions on absentee and early

voting. If that’s so, they sure are

being quiet about it. I keep hearing

that the reason 11% of eligible voters don’t have photo ID (!) is partly that

they can’t get to wherever they need to go to get it. So you would think that MoveOn and David

Axelrod and all those other annoying people I get emails from would be sending

out pleas for volunteers to go drive people to the DMV. Maybe there are sending them to someone, but

none have seeped through my spam filter.

Question 4:

Why is racism so pernicious?

As NYT columnist Bob Herbert said the other day,

the semi-secret Republican subtext in this campaign is race race race. Whether it’s “jokes” about “I was born here,”

or comments about the “food stamp president” or calling Obama a Marxist who

wants radical redistribution of wealth (would that it were true), it all adds

up to the same thing, and it’s all they need to say to trigger the deep fear of

middle-class white older (and not so much older) voters.

Now the people who study these things claim that “race” as

a concept has only existed in human history for a scant six hundred years or

so, that “whiteness” never existed before the importation of slaves from Africa

to this continent.

In the middle of the 20th century, a new generation of historians began to take another look at the beginnings of the American experience. … Their research revealed that our 19th and 20th century ideas and beliefs about races did not in fact exist in the 17th century. Race originated as a folk idea and ideology about human differences; it was a social invention, not a product of science. Historians have documented when, and to a great extent, how race as an ideology came into our culture and our consciousness.

Dr. Audrey Smedley, Virginia Commonwealth University

Professor Emerita, Understanding Race

The role played by America is particularly important in generating and perpetuating the concept of "race." The human inhabitants of the Western Hemisphere largely derive from three very separate regions of the world—Northeast Asia, Northwest Europe, and Western Africa—and none of them has been in the New World long enough to have been shaped by their experiences in the manner of those long-term residents in the various separate regions of the Old World.

It was the American experience of those three separate population components facing one another on a daily basis under conditions of manifest and enforced inequality that created the concept in the first place and endowed it with the assumption that those perceived "races" had very different sets of capabilities. Those thoughts are very influential and have become enshrined in laws and regulations. This is why I can conclude that, while the word "race" has no coherent biological meaning, its continued grip on the public mind is in fact a manifestation of the power of the historical continuity of the American social structure, which is assumed by all to be essentially "correct."

Dr. Loring Bryce, Does Race Exist?

According to Theodore Allen, the knowledge, ideologies, norms, and practices of whiteness and the accompanying "white race" were invented in the U.S. as part of a system of racial oppression designed to solve a particular problem in colonial Virginia. Prior to that time, although Europeans recognized differences in the color of human skin, they did not categorize themselves as white. I will provide more detail later. For now, the important element of his theory is that whiteness serves to preserve the position of a ruling white elite who benefit economically from the labor of other white people and people of color.

Judy Helfland, Constructing Whiteness

So why does such a relatively recent, artificial concept have such enormous staying power, not only in this country, where it was (ostensibly) born, but in many places around the world?

More on that some other time, unless one of you can supply me with the answer.

No comments:

Post a Comment